Richard Feynman's Tips on AI

Rote Practice Still Matters

I lied. Feynman didn’t have any tips on AI. He did have some tips on learning physics though. I think they are good tips on learning anything, and becoming good at it.

Spoiler Alert: Rote Practice Still Matters.

I was introduced to Richard Feynman by my high school physics teacher in Los Angeles, Mr Bunning. Mr Bunning was pretty straight-laced guy most of the time, but he loved to teach and he had an extraordinary love of physics. His mischievous side would come out whenever he spoke about Feynman, which he did quite often. Mr. Bunning regularly played excerpts from Feynman’s famous Lectures on Physics. I still remember an excerpt showing Feynman playing bongo drums.

Mr. Bunning always started class on time. Every morning at 8am sharp. After all, Physics was serious stuff.

One day — several weeks into the course — Mr. Bunning started late. We kept looking at the clock: 8 am…8:05 am…tick…tick.. What was going on? He was fiddling around in the back of the classroom. At 8:10AM or so, Mr Bunning brought an old phonograph to the side of the classroom, placing it next to the pulleys and inclined planes. He then turned it on and played an LP. It was the finale to William Tell Overture and it was very loud. As the notes began to play, Mr. Bunning slowly walked over to the chalkboard and wrote in very big letters:

We were at the edge of our seats. He walked back to the phonograph, turned it off, and returned to the front of the classroom. With a big smile on his face, he said:

“Everything we have been learning for the past several weeks culminates in this one simple equation. These four symbols govern the Universe. Let me now show you.”

Mr. Bunning proceeded that morning to pull the strands together of what we had been learning. The grand synthesis was Newton’s laws. Now, vectors made sense. So did the relationship between Newton’s Three Laws, including the law of gravitation. I was hooked. This was certainly better than any action movie. My college entrance essay, the following year as a senior, was on “Simplicity in Newton’s Laws and Maxwell’s Equations”. Thinking about the day still gives me goose bumps.

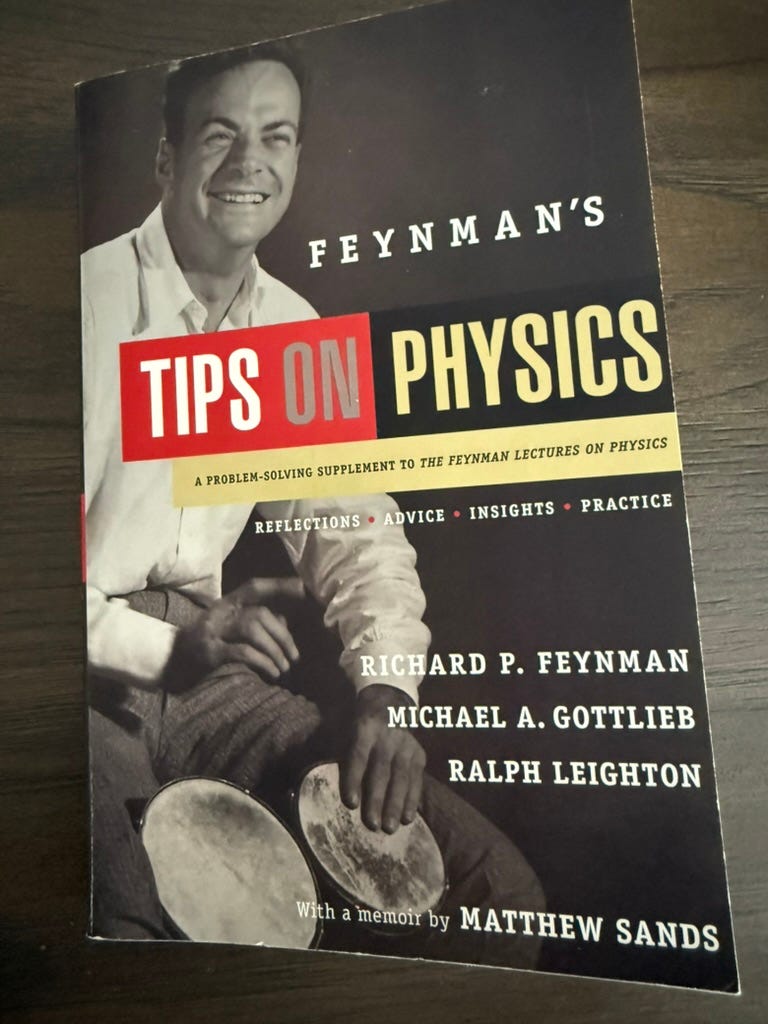

After graduation and much later, I was able to afford to buy Feynman’s three volume lecture set, affectionately known as the “red books”. Many years later and after Feynman’s death, I came across a companion book “Feynman’s Tips on Physics: A Problem-Solving Supplement to the Feynman Lectures on Physics.” (The good folks at CalTech have made the entire series available online for free, including the lecture tips.) On the cover, Feynman is still playing the bongo drums and inviting students to study Physics.

The Missing Lectures and “Funny Feelings”

How did the companion volume come about? It’s a long story, but apparently Feynman gave some additional lectures which never made it into the “red book” lectures. The reason is that they were optional review lectures intended for students having difficulty in the class. In these lectures, “With characteristic human insight, Feynman also discussed the solution to another kind of problem, equally important to at least half the students in his freshman class: the emotional problem of finding oneself below average.”

In one of the review lectures, Feynman takes on this “funny feeling” of feeling below average. “Even if you’re one of the last couple of guys in the class, it doesn’t mean you’re not any good.” Then Feynman gets down to business.

Now, mathematics is a beautiful subject, and has its ins and outs, too, but we’re trying to figure out what the minimum amount we have to learn for physics purposes are. So the attitude that’s taken here is a “disrespectful” one towards the mathematics, for sheer efficiency only; I’m not trying to undo mathematics.

What we have to do is to learn to differentiate like we know how much is 3 and 5, or how much is 5 times 7, because that kind of work is involved so often that it’s good not to be confounded by it. When you write something down, you should be able to immediately differentiate it without even thinking about it, and without making any mistakes. You’ll find you need to do this operation all the time—not only in physics, but in all the sciences. Therefore differentiation is like the arithmetic you had to learn before you could learn algebra.

Incidentally, the same goes for algebra: there’s a lot of algebra. We are assuming that you can do algebra in your sleep, upside down, without making a mistake. We know it isn’t true, so you should also practice algebra: write yourself a lot of expressions, practice them, and don’t make any errors.

Errors in algebra, differentiation, and integration are only nonsense; they’re things that just annoy the physics, and annoy your mind while you’re trying to analyze something. You should be able to do calculations as quickly as possible, and with a minimum of errors. That requires nothing but rote practice—that’s the only way to do it. (emphasis mine) It’s like making yourself a multiplication table, like you did in elementary school: they’d put a bunch of numbers on the board, and you’d go: “This times that, this times that,” and so on—Bing! Bing! Bing!

Feynman then goes on to present a variety of problems that students need to master through rote practice. Bing! Bing! Bing!

What would Feynman have said about AI in Education?

“Remember. Bing! Bing! Bing! There are no shortcuts.”

Mr Bunning would have agreed. So would all the amazing teachers I have had through the years.